Scripture and Tradition

On the authorities we trust (part 1/2).

What is the right way to live?

This is the question. And for those seeking the answer, they ask a second: Where do I go to find out… who or what do I trust to tell me?

The apostle Thomas wondered this question, and asked on behalf of the confused followers of Jesus: “How can we know the way?” Jesus gave a simple, yet enigmatic answer: “I am the way — even the truth and the life!”1 (John 14:6)

Ever since Jesus left the apostles, his followers have searched for how to live “the way” in absence of Jesus, and discovered there were many places to find it — many places that “Jesus” could be found… many revelations of the “way” and “truth” and “life.” These “revelations” or “sources of truth” included the Torah/Biblical teaching, the natural world, love itself and those who exhibit love, philosophy and theology, conscience/moral intuition, and the promptings of God/guidance of the Spirit. All of these sources have, for centuries, been “listened to” by followers of Jesus, and are (with defensible plausibility) the sources Jesus himself listened to and referred to us.

As the church in the West developed, Christians questioned and debated what exactly it looked like to love, serve, and honor God, and what sources of authority could be trusted to guide us to the answer.

One of the unifying features of Christian thought on the subject has been a reverence for the Biblical texts, and the early church fathers gave frequent reference to scripture to back up their explanations of the “way” (of moral, social, theological, and philosophical claims). This was often done with poetic argument, allegorical associations, and symbolic reasoning, as well as (what we often focus on today) literal 1-to-1 arguments, historical context, and anthropological research.

Scripture and Tradition

In the 16th century, Martin Luther and many of the Protestant reformers developed the doctrine of Sola Scriptura (Latin: Scripture Alone) which holds that the Bible is the “sole infallible source of authority” for Christian faith and practice. This served as a way to reign-in the corruption of the Church institution (holding the Church accountable to the Text itself), in hopes of bringing everyone closer to the true teachings of Jesus and the apostles.

The Anglicans and Anabaptist took an approach described as Prima Scriptura (Latin: Scripture First), which accepts that there are multiple guides for Christians to use in the question of how to live, but that Scripture is still “primary.”

The response of the Roman Catholic Church (in its counter-reformation) was to formalize its own position: that Scripture and Tradition were both of equal worth as authorities.

“Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, first promulgated with His own mouth… saving truth, and moral discipline… [which are] contained in the written books, and the unwritten traditions which, received by the Apostles from the mouth of Christ himself, or from the Apostles themselves, the Holy Ghost dictating, have come down even unto us, transmitted as it were from hand to hand… [and thus we] receive and venerate with an equal affection of piety, and reverence all the books both of the Old and of the New Testament – seeing that one God is the author of both – as also the said traditions… preserved in the Catholic Church by a continuous succession.” —Counsel of Trent, 4th session

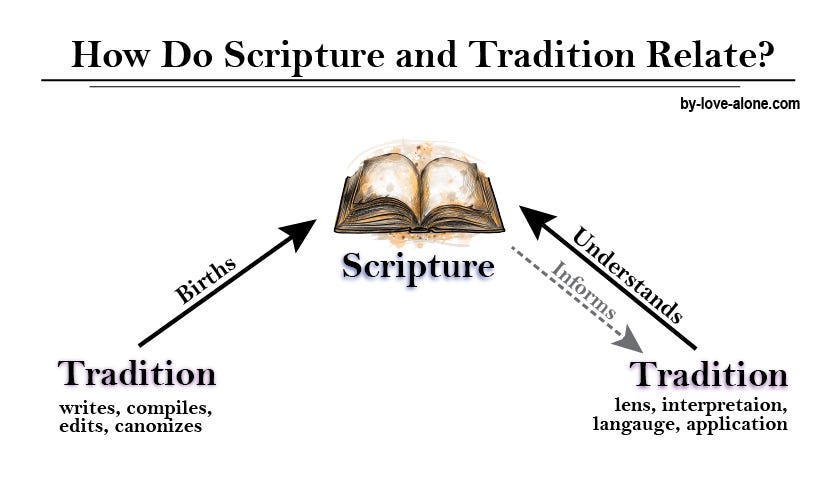

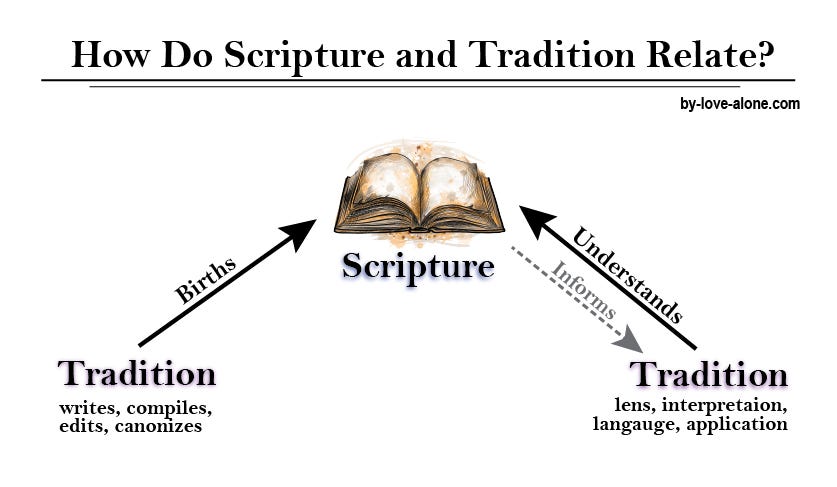

The Bible: A Book Birthed From Tradition

I was raised a good, sola scriptura Protestant. However, this “Bible alone” language no longer seems to me to be the most accurate or helpful way to describe the relationship between Scripture and various other sources of authority. Let’s zoom-in for a moment to consider simply Scripture and Tradition (a hot, intra-Christian debate), it must be recognized, that if we trust Scripture… we are implicitly trusting the Tradition that birthed it. The Bible wasn’t written by one guy… but by dozens (if not hundreds, counting editing hands)… who lived hundreds of years apart. And it wasn’t compiled in a single generation… but over the course of hundreds of years. Many of the texts of the Biblical library were edited and re-edited to serve the needs of the current community as the text was passed-down.

Imagine you’re living within the Jewish word well before Jesus… some scrolls are prominent and have been sacred for generations — like the Torah scrolls of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. You know Exodus the best, because that’s the only scroll your community has (scrolls are very expensive!) but you’ve memorized parts of the others. And you love all the Nevi’im (writings of the prophets) that you’ve heard recited. Certain writings (let’s say Ruth and Ezra-Nehemiah) are currently rising to prominence in your area… and there’s a resurgence of love for the ancient Proverbs… but your area won’t get wind of the Daniel’s scroll or the Qohelet scroll until you’re long gone. Every generation, some writings rise in prominence and others fall… eventually some fall way and are forgotten, but some continue to pass the test in every generation, and are elevated in prominence and authority! Every generation has the opportunity to add notes here, clarify a point there, author an introduction, insert a traditional Psalm, etc.

This process… this organic forming and compiling scripture… is tradition! It’s the custom of the community to revere certain texts and pass them down to their children.

The Bible: A Book Read Through Tradition

Secondly, the Bible cannot be understood except through “tradition.” On the most fundamental level, language itself is a “tradition” formed over many generations and passed-down to us. We must use our “tradition” of language to understand the meaning of the Text. Alongside this, there are also various traditions of how to read and interpret language — there are debates over the proper methods for reading, studying, and applying a text (eg: logical analysis, allegory, dictating, singing together, meditation, authorial intent/context, psycho-social applications, etc). Within Christianity, there are many passed-down traditions of “how to read” the Bible and how to interpret certain passages. The “sola scriptura” tradition was passed-down to me though my Protestant heritage.

Thus, it’s not possible to even understand the Bible, except through the lens of tradition. The diagram below helps to show my thinking on the subject:

This is the end of Part 1. In Part 2, I’ll examine the Wesleyan Quadrilateral.

Feel free to comment your thoughts below!

Photo Credits:

Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash

Graphic created myself.

Notice that Jesus does not say a set of beliefs nor actions are the way… but rather “I am” the way. What is “I am” here? If it’s Jesus, how is it that we walk Jesus… discover Jesus… and live Jesus?